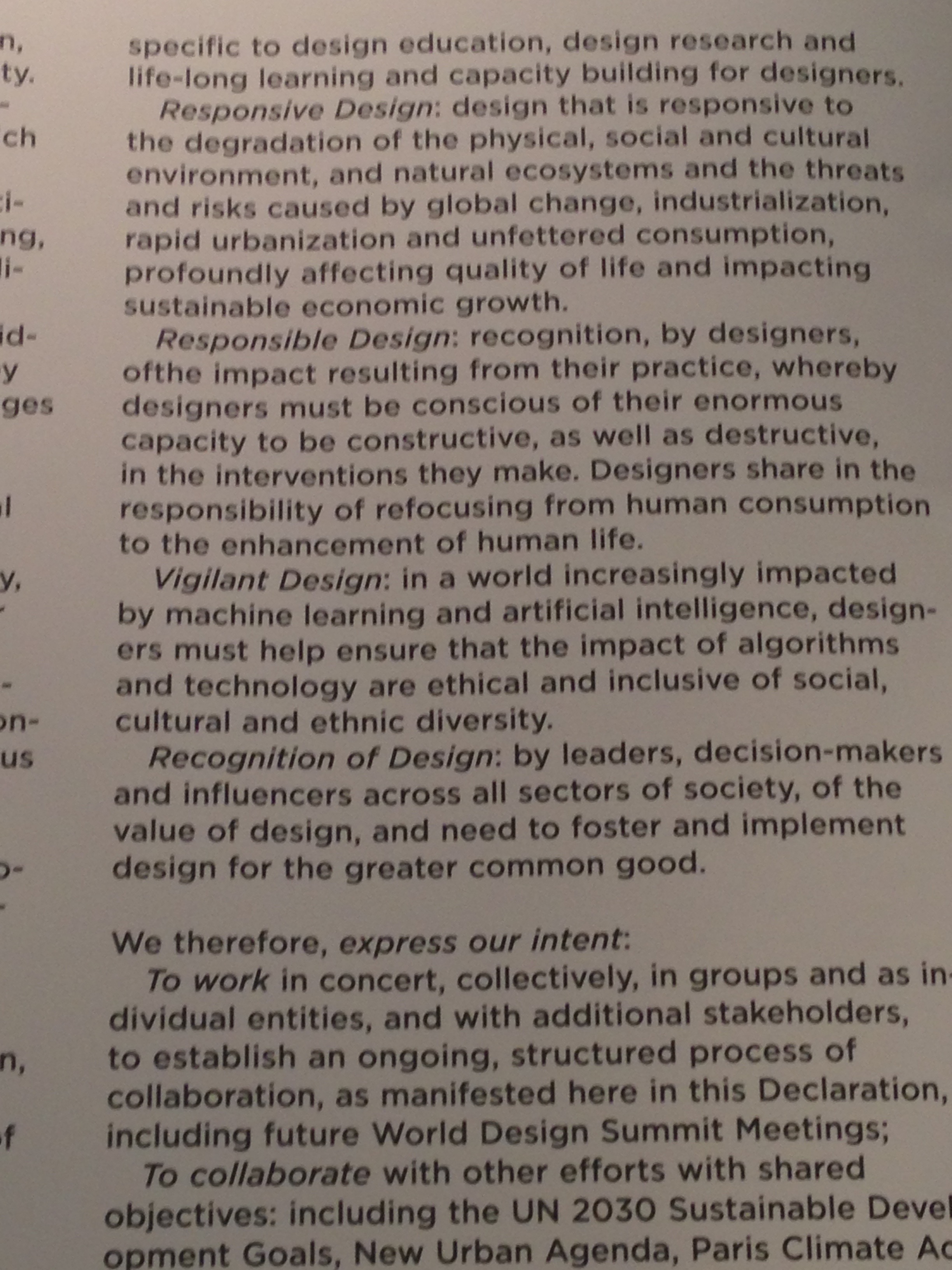

This October I attended the World Design Summit, which brought together professionals and scholars from various design disciplines including: architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning, graphic design, interior design and industrial design. One of the aims of the conference was to break past disciplinary boundaries and open up broader conversations. The MONTREAL DESIGN DECLARATION was issued at the conference in an effort to formalize some of this thinking. The document describes design as a driver and agent of change - one that adds value to projects, expresses culture and facilitates change. It calls for enhancing Design Education, Responsive Design, Responsible Design, and Vigilant Design. I found the tone and language of the document quite vague, which is perhaps the nature of such manifestos, but the lack of detail and specificity means that the document does not address what I believe to be some of the most important issues designers and their clients face today.

A major oversight is that the document does not engage directly with the fact that an absolutely staggering amount of building and production of space happens without the direct or significant involvement of designers. Some estimates suggest that 85% of new construction in the USA is executed mainly by construction forms collaborating with real estate developers and private clients, with only cursory involvement of designers. The Declaration does not in any way address the construction industry, development forces, or the real estate market. Yet, in order for designers to have a significant impact on sculpting living environments, we need to learn how to make convincing arguments that we can add value to projects, and meet the bottom line that is of ever-present importance to developers and municipalities. This means that we need a direct connection and conduit to the main decision makers – municipalities, politicians, policy makers – so that they do not default to looking directly to developers to make urban projects happen. Certainly this is a very difficult and complex task to take on, yet we must make some inroads in to the construction industry, which has remained largely unchanged over many decades, invests little in research and development, and operates with the logic of readily available modules and materials that are easy to transport and store (Goldhagen, 2017 p.30). A significant change to our built environment will only happen when we change the way that the construction industry operates and challenge the relationship between developers and the city, possibly even through new forms of land tenure and land management.

This has many implications for design education; it must involve training in business, planning, economics, and community organizing. While it is somewhat revolutionary that we are finally having discussions about “interdisciplinary” training, in terms of different aspects of design (architectural, landscape, industrial, urban), this is an incredibly small step. Designers are not equipped to deal with pressing issues affecting large swaths of the global population, especially in light of the refugee crisis and migration caused by climate change. Design education needs to be broadened to encompass fields like sociology, anthropology, environmental psychology, and ecology.